Triggers, Jouissance and Rethinking Freedom

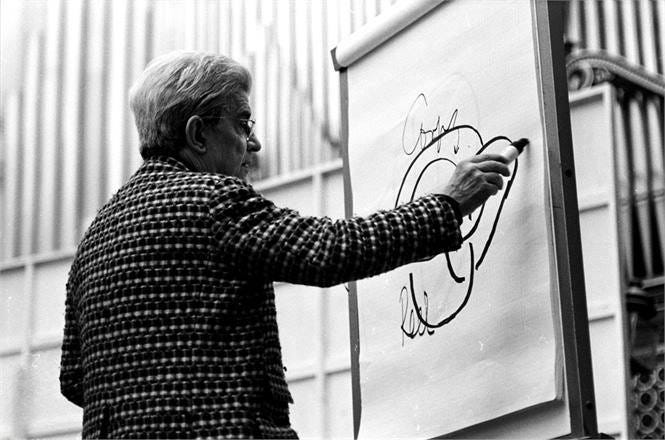

Group Analysis with Macario Giraldo

Macario Giraldo, the Lacanian group analyst, joined us on the podcast this January. I expected to talk about his life and decades in group work. All of that is in the episode. But as I prepared this newsletter, one thread of our conversation stood out because it touches something many of us quietly wrestle with:

Why do certain moments pierce us so deeply, and why do they stay with us?

Macario offered a Lacanian way of understanding this, and I found myself pulled into it.

Triggers and Causes: The Pain Beneath the Moment

Most of us assume the thing that upsets us…the look, the tone, the silence…is the cause of our suffering. Lacan says otherwise. These moments are not causes. They are triggers, small sparks that ignite something already within us. They don’t create our pain; they reveal where the pain already lives.

To explain this, Lacan takes us back to the beginning. We start life in a wordless sense of wholeness. When language arrives and the “I” forms, that fullness slips away. What remains is what he calls lack, a built-in “missing piece” that shapes everything we desire. We spend our lives reaching for things we hope will restore that early fullness, but the longing is never about the object itself. It’s about what it represents.

That’s why triggers matter.

A Simple Example

You send a friend an important text.

They read it, say nothing for hours, then reply with, “Sorry, busy day.”

One person shrugs.

Another feels gutted.

The difference isn’t the text.

It’s the older wound it brushes against, maybe the childhood fear of being forgotten, or the belief that attention equals safety. The friend didn’t cause the wound; the moment simply touched it. What rises isn’t new pain. It’s familiar pain. And that familiarity is exactly what shows us where the real work is.

Locating the Source Inside Is Not Blame. It’s Liberating.

To say that our reactions come from within is not self-blame. It’s pointing toward the only place where genuine change can occur. When we stop assuming the world is “doing this to us” and recognize that life is stirring something already inside, something loosens. We don’t need every interaction to be perfect. Curiosity emerges. And in that shift, transformation begins.

We stop fighting everyone who brushes against our wounds.

We stop believing emotional peace requires perfect conditions.

We begin working with the deeper structures of our desire.

Freedom isn’t eliminating triggers. It’s befriending the parts of ourselves they reveal.

This brings to mind Shantideva’s old metaphor: the world is full of thorns. We can try to cover the earth in leather, or we can simply make a pair of sandals, paraphrased from The Way of the Bodhisattva…

Jouissance: The Too-Muchness We Keep Reaching For

Macario and I then turned to jouissance… one of those Lacanian concepts that sounds complicated until you realize you’ve lived it a thousand times.

Jouissance is not just pleasure. It’s the intensity we return to even when it overwhelms us. It can feel like touching the edge of the sun, too bright, too hot, yet irresistible. Or like trying to hug a memory, it’s impossible to hold.

Sometimes joy, sometimes pain, often both at once. It is the too-muchness we won’t let go of.

Macario spoke of surplus jouissance, the overflow that reason and language can’t digest. This excess seeks boundaries because without limits, it swallows us.

And here psychology spills into politics.

Why We Long for Freedom and Also Long for Limits

In 1968, Lacan told a group of revolutionary students, “What you aspire to as revolutionaries is a new master. You will get one.” He wasn’t mocking them, though you can practically see him saying it: the black turtleneck, cigarette, that unmistakable French philosopher confidence.

He was naming a truth: beneath the desire for total freedom lies a longing for containment. Unbounded intensity is unbearable. We see it in bingeing, in chasing highs that collapse into lows, in teenagers testing limits while secretly needing them, in revolutions that slide into new forms of authoritarianism. When we can’t regulate our own overflow, we reach for someone or something that will.

This may seem contradictory to the idea that freedom comes from within, but the two actually belong together. We need limits. We simply don’t need them to complete us. Freedom grows when we stop outsourcing our wholeness, and limits hold us while we do the work only we can do.

Listening as a Human Antidote

At this point, Macario returned to something beautifully simple: listening.

In a Lacanian sense, listening is a kind of limit. It’s a way of being present without taking over. It isn’t fixing, interpreting, or steering. It is creating a space where the other person can hear and recognize themselves. To listen is to refuse the position of the “one-who-knows”.

When we stop managing another’s experience, the wound beneath their trigger finally has room to reveal itself.

Where This All Comes Alive: Group Analysis

Macario grounded all of this in the place he knows best: the analytic group.

Group analysis is where these ideas stop being theory and become lived experience. In groups, truth doesn’t get handed down. It emerges. The unconscious doesn’t sit inside one person; it moves within and between people.

There is a particular aliveness here. There is the freedom to speak honestly, to hear and be heard, to be challenged and changed, to discover something true in real time. Groups don’t replace inner freedom; they help bring it into being. They offer the shared presence and shared limits that help us hold our own intensity and understand the deeper causes that triggers reveal.

Groups don’t fix us.

They reveal us.

And in that revelation, we glimpse what it means to be human together.

Closing

My conversation with Macario reminded me why I do this work. It invites us to rethink freedom, listen more deeply, be honest with ourselves, and find moments of wonder inside the pressures of modern life.

Freedom is not the absence of limits.

It is awakening within them.

—Elizabeth